Researchers at ETH Zurich have developed a new type of mechanical sensor that could eliminate the need for batteries to power sensors that require a constant supply of power. Their new sensor is powered by sound waves that cause it to vibrate, providing sufficient energy to generate a tiny electrical pulse that switches on an electronic device that has been switched off.

“The sensor works purely mechanically and doesn’t require an external energy source. It simply uses the vibrational energy contained in sound waves,” Johan Robertsson, a geophysics professor at ETH, said.

The system is controlled by tuning the sensor to distinct sounds – in the prototype, for example, the spoken words “three” and “four.” The team is currently working to create new variants of the sensor that will be able to distinguish between up to twelve different words, such as standard machine commands like “on”, “off”, “up,” and “down.” They also seek to miniaturize the palm-sized prototype, to one about the size of a thumbnail, or even smaller.

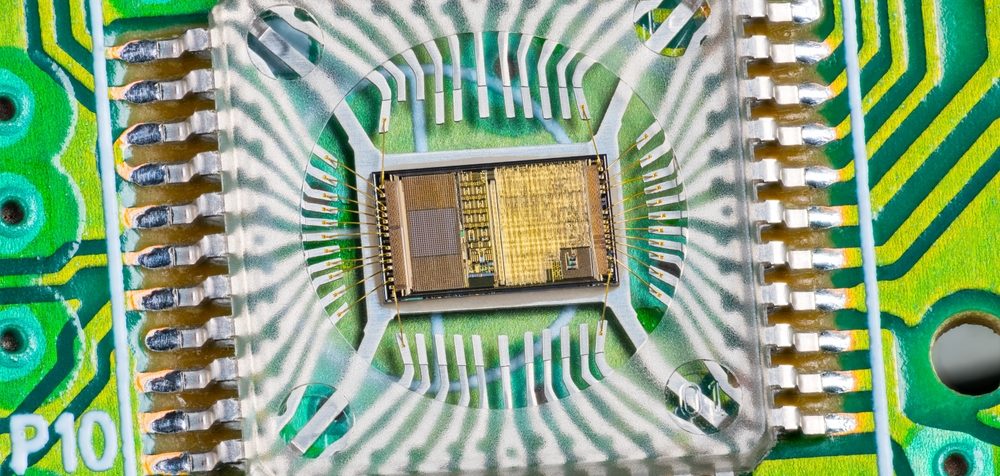

The sensor is made up of dozens of similarly structured plates that are connected to each other via tiny bars, which act like springs. These springs are what determines whether or not a particular sound source sets the sensor in motion.

“Our sensor consists purely of silicone and contains neither toxic heavy metals nor any rare earths, as conventional electronic sensors do,” stated co-author Marc Serra-Garcia.

The tem envisions a number of potential use cases for these battery-free sensors, such as:

- earthquake or building monitoring – registering when a building develops a crack that has the right sound or wave energy

- monitoring decommissioned oil wells – by detecting the sound of gas escaping from leaks in boreholes and

- As a sensor for medical implants – such as providing a permanent power supply for signal processing from batteries in cochlear implants.

“There’s a great deal of interest in zero-energy sensors in industry, too,” Serra-Garcia added, who continues working on a solid prototype at AMOLF. They expect to complete the project by 2027. “If we haven’t managed to attract anyone’s interest by then, we might found our own start-up.”